A Trip to the Brainforest

Birds, Brains and the Scientific Search for the Soul.

Close Encounter With an Identified Flying Object

My friend and I were on a road trip, driving on the freeway through farm country. Suddenly a huge flock of birds rose out of the field ahead of us and flew directly across our path.

“What the hell is that?” he yelled.

I thought for a moment and said

“It’s a Martian!”

My friend laughed. Of course it was a joke. But it got me thinking: if Martians ever visited us, would we really know what they are? Why should we expect them to look like those angry little green bulbous-headed men that we see in low-budget 1950’s movies?

Why not a flock of birds?

Have you ever wondered about what a flock of birds actually is? I mean, just on the level of physical objects. If we see a bunch of birds flying by us we can pretty easily say, “Yup, that’s a flock of birds”. But what happens when a bunch of them head off in another direction? Where is the flock now?

Years later, the same question arose again while I was relaxing with a book on my back deck one sunny afternoon.

The bird feeder was empty. Below it, the tossed seeds had all been plucked off the ground. A lone sparrow came by to inspect the feeder, just in case. Nothing there. He tried the ground below, just in case. At the moment he touched earth three more sparrows joined him.

And then the tree released a flood of hungry birds within an instant. The ground was rippling with a mass of sparrows, searching for grains that might have been forgotten from previous visits.

One bird got nervous (as small birds seem to do). He flew back to the tree, pulling along two others as if joined by elastic. But there was no mass exodus - because another sparrow countered the retreat by joining the crowd. But that didn’t last long. Another bird gave up the search and took flight. Two or three others exited as well, just in case. The process of exits and arrivals continued for a minute or so.

I had an itch on my head but I dared not move. Just in case.

Birds arrived singly and left in small groups. It was a liquid exchange which dripped down and up, all at once. A bicycle chain clicked in the next yard. The tree instantly sucked the tiny adventurers back into its leaves. Finally I could scratch my head. The tree shouted with a hundred voices “Are you still there? Yes I’m still here!”

You can’t see birds in a tree on a summer day because of the leaves. If the tree were made of glass, you might see the birds hovering in space, like a galaxy. Part order, part chaos.

But beyond the physical closeness, the birds behave like a single unit. The flock. The group. The galaxy in the tree. They have evolved to survive as a group. Their brains play a key role to unite them as a ‘social being’. They constantly talk to stay together. They hear each other. They observe each other. They follow each other. They are not unlike us.

Socially, our brains have the ability to act together to make groups of individuals become part of a social being. The crowd at a sport stadium. The fans at a concert. The protestors on the street. Society in general.

What is perhaps more interesting is that our brains also do the same thing internally. Billions of neurons act together to form coherent patterns and achieve specific results.

The Scientific Search for the Soul

When I was sitting on the deck watching the birds that day, the book I was reading was ‘The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul’. It is written by Sir Francis Crick who won the Nobel prize for his role in discovering the structure of DNA molecules. The latter phase of his career was focused on theoretical neurobiology. This apparently spawned a keen interest in the science behind human consciousness.

Crick’s book was my first ‘deep dive’ into neuroscience. I had glanced at it in art school when a friend showed me some books he’d unearthed in the psychology library. It introduced the idea of neurons being responsible for perception - which intrigued me as an art student who was tasked with learning how to see things in new ways.

There was one other slightly odd thing that happened in my last year of art school that prepared me for reading Crick’s book decades later. Somewhere, in one of the many art books I’d been obliged to read through, I came across an intriguing statement by an artist. He said ‘we can never define meaning’.

My final year of art school was, if I’m really honest, a disaster. I didn’t fit into any of the official disciplines. I was an academically displaced person. And a bit of a fighter. So I took that artist’s declaration as a personal challenge. I spent a long time thinking about it. Weeks? Months? I came up with this:

Meaning = Continuity

I could go on a lot about this but for now I’ll just say that it mostly has to do with identity. Whenever we identify ourselves in a certain way, specific choices, experiences and insights become ‘meaningful’. These meanings go directly to help the identity persist, to continue. (Think about this: we often define the meaning of life in the context of an afterlife - more continuity. It is almost impossible for many of us to conceive of complete discontinuity - a real dead end.)

So I brought my definition of meaning along for my journey into the scientific search for the soul, led by Sir Francis Crick.

Crick comes out strong on page one. He leads with a quote from the Roman Catholic catechism “the soul is a living being” and then in his first paragraph, presents his hypothesis. It is that you, and everything you identify as yourself including your joys, sorrows and free will, are ‘no more than’ the behaviour of a huge collection of neurons (nerve cells) and their related molecules.

I’m not religious, so I don’t get upset by scientists when they make claims like this. I have no investment in beliefs about the soul and no religious dogma to uphold. But to be honest, I’d like to think there is more to it than just that. That is a big reason for my writing here - to explore this question.

This article is the third in a series that introduces the concept of Core-Radiance. You can find the other two articles here:

Entering the Brainforest

What I like about scientists is that they, like dancers, can’t fake what they do. The work of scientists is evaluated by peers with the high benchmark of providing evidence, logic and proof. They can’t bullshit their way into credibility. Dancers can’t either. If they can’t move in a way that honestly connects with the music and the environment, they will not be regarded as ‘real’.

So I can relate to that. And Crick’s hypothesis aroused my interest. But as an artist, I wouldn’t just rely on ‘logic’ and ‘proofs’. Between all that I believe and all that I can prove is all that I feel. Intuition matters. I start with intuition and find proofs later.

It’s no coincidence that I made those careful observations about birds in my back yard as I was reading a book about neuroscience. My intuition sensed a connection. Here’s what it led me to understand: the brain is like a combination of the trees and the birds, acting together, all at once. Somehow.

I’m not saying this just to be cute. I’m using the technique of metaphor to build an understanding of something that is pretty complex.

The brain is made of billions of neurons. Loosely speaking, each neuron has the same type of shape as a tree:

Roots - Trunk - Crown (branches)

Dendrite - Axon - Axonal arbor

Interestingly, the word ‘dendrite’ comes from the Greek ‘dendron’ which means ‘tree’. So scientists are fully aware of the tree-like shape (they call it ‘morphology’) of a neuron. When they say ‘axonal arbor’, they are saying “Hey this neuron looks like a tree - look at the branch-like patterns of the terminals!”

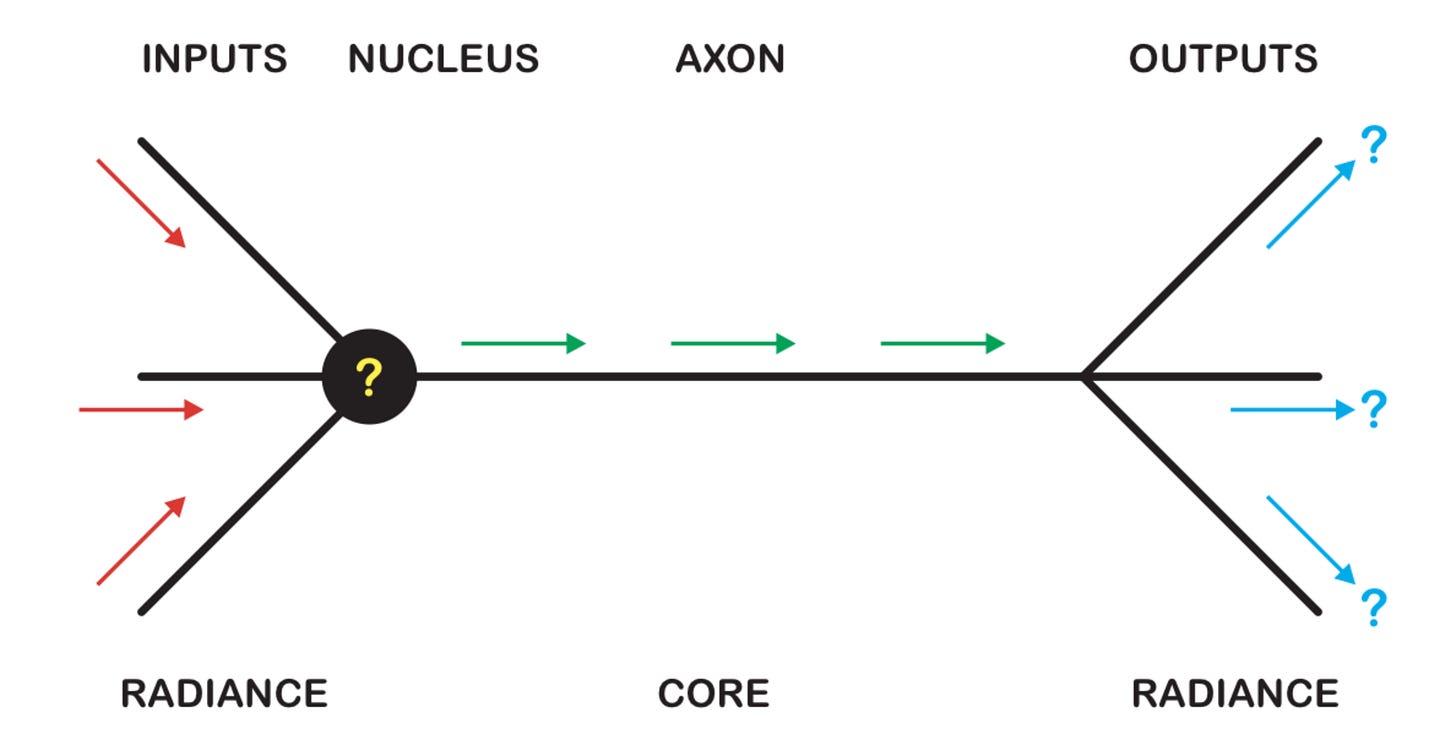

So neurons, being amazing structures that evolution has come up with for building brains, actually focus electrical impulses from one space and redistribute them to another space and along the way they make decisions about when to do it through a kind of centralized ‘voting machine’ (the cell body).

Space - Focus - Space

In my first article of this series I described the shape of trees as being somewhere between chaos and order. And this comes from the interfusion of two kinds of ‘energetic forms’ - Core energy (the trunk) and Radiant energy (the branches). I find it fascinating that the building blocks of the brain use the Core-Radiance principle in order to make the brain actually work.

Radiance - Core - Radiance

Here’s a schematic diagram:

A tree connects two ‘spaces’, earth and sky, to provide the essential nutrients and solar energy it needs to live. Similarly, neurons connect different spatial contexts as an essential part of their function.

The job of a typical neuron is to take in ‘signals’ from multiple inputs and make a go/no-go decision to fire - i.e. pass a new signal along to a vast number of targets. By doing so, it makes connections across different spaces. The ‘tree-like’ shape makes all the difference - without it, the connections would be just point-to-point and brains would never work.

As a system of billions of structurally connected neurons, a brain establishes patterns of continuity. It turns information into meaning. The meaning helps ensure the survival of the brain owner.

Which body position represents dance?

Reading Crick’s book was a turning point for me. He made a very complex subject relatively understandable. His hypotheses grabbed me from the start and he followed through with insights about the brain that truly fascinated me.

Having made it clear throughout the book that the brain does not work as an internal projection screen with some ‘little person’ inside watching it, Crick explains that the brain breaks things down into countless diverse features such as colour, edges, shape, motion, etc.

Crick then poses the question of how the brain puts it all back together. How does it integrate the various features to arrive at a perception of an ‘object’? He calls this the ‘binding problem’. How are the ‘loose ends’ bound together into a ‘thing’?

When drawing, artists can do that through hatching. We draw a series of equally spaced parallel lines in a given area to, kind of magically, suggest solidity - this is a ‘thing’! The key is the rhythm. If you use non-equal spacing the effect doesn’t work. It’s just more noise. The object falls apart. That’s first year art school stuff.

So, as I read Crick’s book, I started pencilling the words ‘binding rhythms’ in the margins whenever he talked about building objects in the brain.

His chapter on ‘Visual Awareness’ delves further into the problem of relating neurons to ‘objects’ and, at the time of the book’s publication, there were not many solutions. Throughout the book, the problem is defined in terms of mapping outside objects to single neurons or groups of them. The technical term used for this is ‘neural correlate’. This book is about Crick’s search for the neural correlate for consciousness. The scientific search for the soul.

But searching for a neural correlate for anything is like asking which body position represents dance?

In other words, why should there be a single end point of resolution for our experience of things we can recognize or label as ‘objects’? Look at the photo below. How many ‘objects’ do you see?

Look longer. How many more do you see? Why should your ability to perceive objects in this arbitrary scene be tied to neurons that were sitting around doing nothing until now? Or if they were doing something before, then how have they now come to ‘represent’ these arbitrary objects. The idea is basically absurd.

And Crick himself knew that. He repeatedly states there just aren’t enough neurons to make things work this way. But that was the ‘state of the art’ of neuroscience at that time.

But something else didn’t add up. A neural correlate is a neuroscience equivalent to Grand Central Station. It’s a sort of point of arrival. But it’s a dead end.

This contradicts an important feature about the structure of neurons - they always have outputs. There are no dead ends. So how can there be a point of arrival? For years I wondered, where the heck do things go from there?

When I eventually found an answer, it was remarkable.

Coming next week, Finding Paths of Return in the Brainforest

This article is the third in a series that introduces the concept of Core-Radiance. You can find the other two articles here:

References

- Francis Crick, *The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul* (Scribner, 1994)