The Big Bang Theory of Trees

A Gift from the Universe (I Almost Ignored)

I was in art school when I first saw trees in a way that changed my life. This moment of vision triggered a chain of discoveries about art, science and human relationships.

In my teenage years, I was a very good painter. I began taking art classes at the grade 12 level, when I was in grade 10, still majoring in Industrial Arts. In the following year, my teachers supported me by creating a grade 13 course so I could continue. They even gave me a private studio, under the auto-shop. It was a great place to work on my paintings, the record player blasting Frank Zappa and Miles Davis. I was inspired.

I was largely self taught - the art teachers offered their feedback but little technical advice. Other teachers commissioned paintings from me. I made a killing at $25 per landscape-in-oils. In the summer before my last year of high school, I attended a university art course in my home town of Manchester, England. This was more of a challenge. The professor running that course, opened my eyes to many things. He taught me how to see more analytically. I am forever grateful for this.

While in England I had a chance to visit the National Gallery in London where I encountered Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Madonna of the Rocks’. Da Vinci had been my inspiration since I was a young boy. So it was inevitable that after seeing his painting in London, I would attempt to do the same. This is what teenagers do.

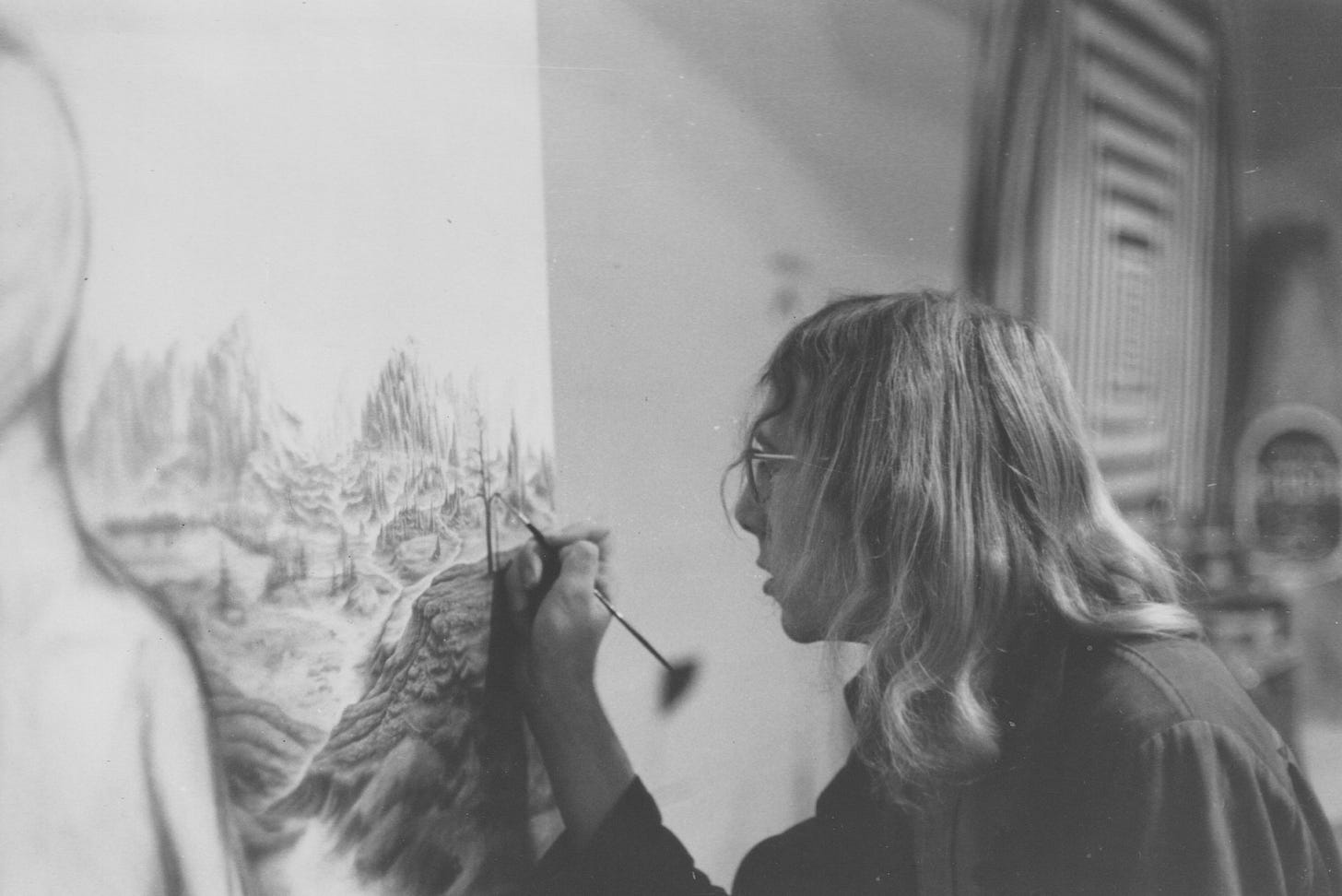

I spent my final year of high school working on a huge painting that was to be my ‘Madonna of the Rocks’. I had it all worked out: how to do the mountains, how to do the trees, etc. But I did not know how to solve the problem of the main subject - the scantily clad woman in the foreground. As a 17 year old, I did not have access to half-naked women to pose for me. So that area remained blank.

When I began university art school, I naively brought that enthusiasm for Leonardo with me, along with my unfinished ‘masterpiece’. My fellow students were impressed. My professors were repulsed. Their preference (i.e. their entire focus) was Abstract Expressionism, which, in my view, was another label for bank lobby art.

I had no interest in making corporate artwork. Within a year I had lost my love of painting entirely. My ‘masterpiece’ was never finished. By second year, I had turned my attention back to Industrial Arts - spending most of my time skipping classes to make a perpetual motion machine that plugged into the wall socket.

By third year I was hanging around the Electronic Engineering building and doing literal dumpster dives to retrieve discarded printed circuit boards and various other objects of technological beauty.

By fourth year, I was a complete outcast, being neither a painter, a print maker nor a sculptor. For a time I set up a ‘studio’ in the front lobby of the art building. Then in a hallway outside the campus post office. Eventually I moved to the back of the wood-shop, separated from the dust and the noise by a large, thin sheet of polythene.

In terms of image-making, the only activity that stirred my interest was drawing. I did it entirely on my own time, privately working on the street, far away from the school studio. It allowed me the freedom and time to make in-depth studies of my subjects.

I made detailed drawings of historic buildings in my small campus town. To earn extra money, I sold high quality reproductions at local book stores.

One of the things I learned from the professor in the Manchester art course was that when we draw, we are not just making pretty pictures. We are attempting to gain an understanding of our subject. The pencil marks are like notes. Drawing is an analytical tool.

If the mind is well focused and the eyes are clear, the pencil lines convey critical information about what we are seeing. I analyzed many picturesque streetscapes in that university town. But, over time, I focused more and more on the trees. One might say the trees drew me. The old historic buildings became just an excuse to examine and understand the surrounding trees.

For my small business, I made a series of half a dozen reproductions of my drawings. Of that set, the most popular by far was the old campus concert hall with its signature tall clock tower. It sold out.

I believe it was popular because of the way I had captured the surrounding trees.

I took my time with this one. For three days I had sat with my easel at the edge of the road, mapping what I saw with as much precision as I could manage. Taking note of exactly where the tree branches were distributed in space.

There is little ‘expressiveness’ in this image and zero abstraction. I was not interested in making art for its own sake or romanticizing the scene. I had taken on the task of truly understanding the shape of trees. I suppose I had approached it with the eye of a scientist.

After each session, as I walked home, every tree I saw began to look a little bit different.

First I saw their unique shapes.

Then I saw their energy.

Suddenly my eyes realized that trees are actually seeds exploding into the air. Time seemed irrelevant.

I saw the structure of every tree. I saw the way the trunk thrusts upwards out of the ground. I saw the branches flying out from the centre.

I saw the tell-tale signs of an exploding mass. It was just happening over many decades. For me it was like discovering ‘red shift’ where each tree was its own universe with its own Big Bang.

Seeing trees in this new way was a visceral experience. It was all about energy. It was a gift from the Universe.

As spectacular an experience as it was to see neighbourhood trees exploding, I sensed something else was going on. Intuitively, it felt like there were messages encoded into these forms. And I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

So I mentioned it to my brother. I tried to explain what I was seeing but words failed me. Unlike me, he was skilled in mathematics and found my mumbling somewhat annoying. But before he could abandon the conversation, an idea clicked and he said something that changed my life.

“There’s an article in this month’s Scientific American. It’s about a new branch of geometry that explains the mathematics behind natural forms.”

This was 1978.

Geometry? Maths? I hated maths. I had dropped out of mathematics in high school so I could make more art. But science? Yes I was always interested in science. After all, Leonardo was both an artist and a scientist.

I bought a copy of the April edition of Scientific American. Luckily it was still on the shelves.

The article, now a classic, was by Martin Gardner under his “Mathematical Games” column. It focused on the creation of stochastic (random) music introducing the remarkable work of a physicist named Richard F. Voss who worked at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Centre.

The article, being focused on music, showed how melodies could be generated using a certain type of randomized pattern called ‘1/f noise’ (one over f noise). This pattern was somewhere between ‘white noise’ (completely random, completely incomprehensible) and ‘brown noise’ (very orderly, very boring) Putting it briefly, it described a way to measure the interfusion between order and chaos. Between order and surprise. And, when you think about it, that is exactly what music is.

There were 2 remarkable things about this article:

First, was the extent to which Voss’s work could be applied to both human understanding of ‘art’ and patterns found in nature. The article focused a lot on trying to link the two.

Secondly, the article, almost as an aside, introduced a new mathematical field - fractal geometry. It was developed by another member of the Watson Research Centre, Benoit Mandelbrot. The reference to fractals was really just as supporting material for Voss’s work.

Interestingly, over time, very few have heard of Richard F. Voss but the name Mandelbrot has become a household word in certain circles. And fractal geometry has changed our world in ways far beyond our comprehension.

I made a special-order for Mandelbrot’s book ‘Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension’. When it arrived, weeks later, I pored over the pages, ignoring the extensive mathematical formulas and fixating on the computer-generated imagery. Most striking were the images of mountains similar to those in my unfinished painting, all generated by computer programs.

This marked the point where I put down my paint brushes and turned to the keyboard. In a time when few had heard about ‘personal computers’ I realized that this was my future.

As far as my ‘tree epiphany’ was concerned, a good part of the mystery was solved. Certainly fractal geometry, as an ‘explanation’ for patterns of nature, did shed light on my new way of looking at trees. But something was missing - I still wanted to know more.

When I had obsessed over the precise details of those trees in my drawings, my aim was not to create pretty pictures. I wanted to understand what forces of nature exist to shape them in real life. So, as interesting as fractals were (I spent the next decade learning software development so I could create ‘natural’ looking imagery) I came to realize that they were not answering my deeper question.

It was decades later that I realized the real answer for me was in the work that Voss was doing with 1/f noise.

Voss had boldly claimed that 1/f noise was behind the meaning of music and art. In my case, it went beyond describing the ‘self-similar’ statistical patterns that defined the fractal geometry of trees. It resonated more with me because it stayed close to those underlying forces behind those shapes. 1/f is not just about pretty patterns. It is about measuring the energy across a range of frequencies and identifying a particular pattern that nourishes our souls.

Energy is the point. The shape of energy is the key.

Trees connect Earth and Heaven. They bring life to the planet. They are graphic examples of 1/f power spectra. And that pattern has a meaning critical to life.

Blending intuition and logic has been a source of discovery throughout my personal and professional life. My approach to drawing trees was an important example of this.

Intuitively, I saw the energy of the trees then and I still see it today. But now I also see that energy in many other places and in vastly different circumstances. The exploding trees were just the beginning.

Logically, careful observation and consideration led me to powerful insights which I have since applied in my work and in forming strong relationships with those around me.

But it would be years before I found a name for what I really saw in those trees - and I found it not in a park but on the dance floor.

References:

- Gardner, M. (1978). “White and brown music, fractal curves and one-over-f fluctuations.” *Scientific American*, 238(4), 16-32.

- Mandelbrot, B. (1977). *Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension*. W.H. Freeman.

- Voss, R.F. & Clarke, J. (1978). “’1/f noise’ in music: Music from 1/f noise.” *Journal of the Acoustical Society of America*, 63(1), 258-263.

Beautifully articulated and inspiring. I look forward to the next article...